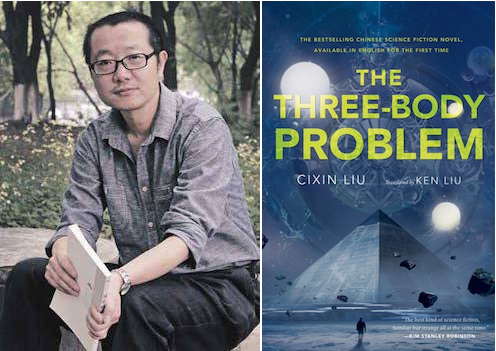

When China began to build its first SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Life) satellite, it called on an unlikely consultant—science fiction author Cixin Liu. The author of the Hugo Award-winning The Three-Body Problem is a sensation in China, regarded as the leader of a new wave of Chinese sci-fi. He also has a dark view of first contact, which won’t come as a surprise to anyone who has read the trilogy: Trying to contact an alien “Other” is risky, he says, because it could bring about our extinction.

The Atlantic has published a fascinating profile on Liu, the observatory, and the larger history of China’s position with regard to outsiders, be they fellow Earthlings or extraterrestrials—all pointing toward the question of What happens if China makes first contact?

What makes the observatory, located in the southwest part of the country, so impressive is not just its size—nearly twice the width of the dish at Puerto Rico’s Arecibo Observatory, which has starred in such sci-fi tales as Contact and The Sparrow—but also its intent: It is “the first world-class radio observatory with SETI as a core scientific goal.” While SETI research in the United States was defunded nearly 25 years ago, it is still kept afloat by private funding; The Atlantic’s Ross Andersen describes how China’s new observatory has been welcomed into “a growing network of radio observatories that will cooperate on SETI research, including new facilities in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.”

But back to Liu’s role as sci-fi consultant. The Dark Forest, the second installment of Liu’s trilogy, is named for a grim but logical theory about the risks of first contact:

No civilization should ever announce its presence to the cosmos, he says. Any other civilization that learns of its existence will perceive it as a threat to expand—as all civilizations do, eliminating their competitors until they encounter one with superior technology and are themselves eliminated. This grim cosmic outlook is called “dark-forest theory,” because it conceives of every civilization in the universe as a hunter hiding in a moonless woodland, listening for the first rustlings of a rival.

Liu isn’t just talking about hypothetical alien encounters. The trilogy draws inspiration, he told Andersen, in part from key historical moments, like the 19th-century invasion of China’s “Middle Kingdom” by European empires approaching by sea. When Andersen challenges Liu that the dark-forest theory may be too rooted in encounters between China and the West to apply on a more interstellar scale, “Liu replied, convincingly, that China’s experience with the West is representative of larger patterns. Across history, it is easy to find examples of expansive civilizations that used advanced technologies to bully others. ‘In China’s imperial history, too,’ he said, referring to the country’s long-standing domination of its neighbors.”

Buy the Book

The Three-Body Problem

The Atlantic’s piece is an impressive profile months in the making: Andersen traveled to China this past summer to shadow Liu and engage in these kinds of thought-provoking debates, while Liu’s involvement with the Chinese Academy of Sciences stretches back even further. It’s really worth reading in its entirety, but here’s another excerpt, from when Andersen asks Liu to entertain the possibility of being called to the observatory in the case of actually detecting an extraterrestrial signal:

How would he reply to a message from a cosmic civilization? He said that he would avoid giving a too-detailed account of human history. “It’s very dark,” he said. “It might make us appear more threatening.” In Blindsight, Peter Watts’s novel of first contact, mere reference to the individual self is enough to get us profiled as an existential threat. I reminded Liu that distant civilizations might be able to detect atomic-bomb flashes in the atmospheres of distant planets, provided they engage in long-term monitoring of life-friendly habitats, as any advanced civilization surely would. The decision about whether to reveal our history might not be ours to make.

Liu told me that first contact would lead to a human conflict, if not a world war. This is a popular trope in science fiction. In last year’s Oscar-nominated film Arrival, the sudden appearance of an extraterrestrial intelligence inspires the formation of apocalyptic cults and nearly triggers a war between world powers anxious to gain an edge in the race to understand the alien’s messages. There is also real-world evidence for Liu’s pessimism: When Orson Welles’s “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast simulating an alien invasion was replayed in Ecuador in 1949, a riot broke out, resulting in the deaths of six people. “We have fallen into conflicts over things that are much easier to solve,” Liu told me.